First World War Project

William GAMBRILL (of Lynsted)

b. 14th July 1889 Trooper, Service Number 1726 |

William was born on 14 July 1889 in Badlesmere to Joseph, a wagoner, and Mary (née Pearsal) Gambrill. He was the youngest of their remaining six children, one having predeceased William. William's older siblings were George, Thomas, Ellen, Annie and Elizabeth. The family moved firstly to Wingfield Farm Cottage, Stalisfield, then to Bogle Farm and then to Lynsted Court, where Joseph worked as a wagoner and William as a farm labourer.

On 28 February 1914, in Lynsted Church, William married Lilian Gertrude Hawkins, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Mercy Hawkins of The Malt House, Lynsted Lane. Their first child, Douglas William, was born on 27 July 1914 and a second, Maretta May, on 8 April 1916. William was also step-father to Lilian's son, Arthur Smeed Hawkins, born on 3 November 1909. William and his family lived in Champion Cottages, Greenstreet, Lynsted and he was now employed as a cranedriver in the paper store of the Sittingbourne paper mill.

William enlisted in the Royal East Kent Mounted Rifles (REKMR) in Sittingbourne on 9 December 1915 and immediately put into reserve. On 9 June 1916, he was posted into the REKMR 3/1st. Then on 25 October 1916, he was transferred to the newly formed Household Battalion1 Reserve, a training battalion, and given his new rank of "Trooper". The men were paid the cavalry rate of pay, a few pence more than the infantry, and they wore cavalry service dress when on leave. William would have trained at the new infantry battalion's Combermere Barracks, Windsor.

[The Household Battalion was an infantry battalion formed on 1st September 1916 and disbanded in 1918. It was formed from the reserves of the Household Cavalry regiments (the 1st Life Guards, 2nd Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards), converting cavalrymen into foot soldiers to help meet demands for infantry on the Western Front. Men of the battalion were paid cavalry rates of pay (a little more than infantry) and wore cavalry uniforms while on leave.]

On 4 November 1916, William completed his training and transferred to the Household Battalion. Just 4 days later, on 8 November, he embarked for France from Southampton. Disembarking at Le Havre on 9 November, the battalion moved to their depot at Honfleur and joined the 10th Brigade of the 4th Division, an experienced formation of the regular army that had been in France since August 1914.

Most of the men of the Household Battalion had undergone little training before they went into the trenches for the first time on 8 December 1916 at Sailly-Sailliesel, east of Combles and Morval in the Somme Valley. The Battle of the Somme had come to an end on 18 November but German artillery fire continued.

The battlefields had become a quagmire and it was recorded that over forty men had to be saved by being dug out. During December 1916 and January 1917 many of the men were suffering from total exhaustion, so it should come as no surprise that William was admitted to the No 6 General Hospital in Rouen on 16 December with trench foot. On the 28 December, he was transferred to a convalescence hospital before being discharged on 1 February back to the depot at Honfleur.

The Household Battalion had now moved to trenches at Bouchavesne but by 17 February 1917 William was back in hospital in Rouen suffering from bronchial catarrh and "pyrexia of unknown cause (fever)". By 27 February he had re-joined his regiment, who were now in a 'rest area' of Arras.

In the lead-up to the action in which William died, the Household Cavalry moved from Bertangles to Beavul and arrived at Villers-L'Hopital on 7 March where they began a period of intensive platoon and company training. Practice trenches were dug for bombing and Lewis Gun classes. Between 11 and 17 March, they moved on again to Petit-Bouret sur Canche, Savy, Laresset and Maroeuil, finally arriving at Camblain-Chatelain for further training and specialist classes. On 8 April, the Battalion marched to Frevillers, from where they went to the front to carry out a scheme of carrying-work before taking part in costly operations on 11 and 12 April. They suffered 150 casualties, four of whom were officers, before retiring to dug-outs. Returning belatedly (the guides had got lost) to trenches on 17 April, they suffered very heavy bombardments and sniping with 4 O.R. killed and 22 wounded; one officer was wounded.

From billets, the Battalion travelled in motor buses on 21 April to Ambrines for Company training. From there they marched into billets north of Arras to prepare for the attack planned for the beginning of May. On 30 April, they moved into Trenches to relieve the 15th and 16th Royal Scots and 10th Lincolns.

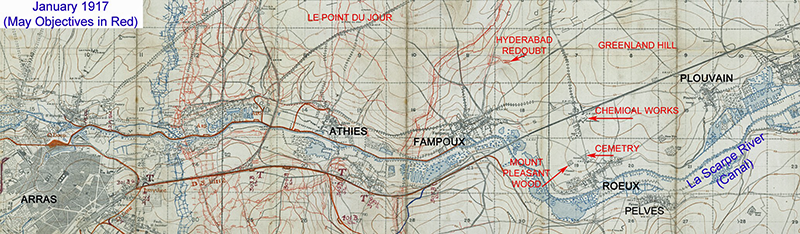

The Household Battalion operations on 3 and 4 May 1917, were intended to seize the two objectives known respectively as the Black and Blue lines. The Royal Warwickshire Regiment was to attack on the left with the same two objectives in view whilst the Somersetshire Light Infantry (attached to the 10th Infantry Brigade for operations) was to take and hold that portion of the Black Line that lay between the right of the Household Battalion and the Scarpe to the East of Roeux village.

The Household Battalion was ordered to attack on a two Company frontage with two platoons in each wave – 1st wave to take 1st objective – 2nd wave to take 2nd objective – half a Company to act as moppers-up for the buildings round the Cemetery and the remaining half to form a defensive flank facing south. [click map for larger version]

On 15 May 1917, Major John H M Kirkwood summed up the actions of 2, 3 and 4 May:

At 9.30 p.m. on May 2nd the Battalion moved into their position in the assembly trenches which had been cleared the whole of the day to allow the heavy artillery to bombard the lines round the Cemetery and Chateau. I visited the front line and Support Trenches and found all the men in position by 11.30 p.m.

Battalion H.Q. was situated at the Embankment (named Crump later).In order to try and keep in touch with the trend of events I sent Lieut Cazalet, as forward observing officer to a spot approximately I.19.c.4.7. together with two signallers who established a line with Battalion H.Q.

At Zero hour 3.45 a.m. it was still very dark and the darkness – as I heard later – was increased by a heavy smoke barrage which caused the waves to begin to lose direction almost immediately.

No reliable information reached me for some considerable time, as my forward observation posts were unable to report anything owing to the smoke and the darkness.

Information from two wounded N.C.O.s, however, pointed to one or two isolated parties having pushed forward across the Roeux – Gavrelle Road whilst the greater number appeared to be held up in front of the Cemetery and in front of the Road South of Corona trench, owing to very heavy Machine Gun fire.

The first authentic report came through the Somersetshire Light Infantry who were almost immediately checked in their advance through Roeux Wood by intense machine gun fire.

In view of this the O.C. Seaforths and I after talking the matter over decided to telephone the 10th Brigade H.Q. to ask for a Battalion to come up in support in order to attack Roeux village from the direction of Mount Pleasant Wood and thus relieve the pressure in the Wood itself, this message was sent at 5.10 a.m., but the suggestion was not consented to.

Soon after this I had an order from the Brigade to send out to my forward posts and tell them to consolidate where they were and also to send out two platoons from carrying Company to support the defensive flank on my right. I was on the point of sending out runners with orders accordingly (5am to 5.30am) when information came through to say that most of my men were back again in the front line trenches. I sent up Lieut Cazalet to clear up the situation and he returned about 6.15 telling me that this was the case and that only one officer – 2nd Lieut Baker had returned. I then ordered 2nd Lieut Wanklyn (6.38 a.m.) with two platoons from my carrying company to go up and re-organize the front line and hold the same sector as we had assembled in. At 10.45 a.m. I received an order from the Brigade to try and push forward scouts to see whether we were holding out near the Cemetery owing to snipers and machine guns this was not possible in the open but a report came through from a Sergeant of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment at 11.7 a.m. to say that 40-50 of the Brigade were holding out along the Roeux – Gavrelle Road – later on we heard that most of these had been taken prisoner by the enemy.

At about 12.30 p.m., I sent forward two bombing parties up Corona trench under 2nd Lieut Wanklyn to work forward as far as possible and then block the trench. This movement was ordered by Lt. Col. Forster – Royal Warwickshire Regiment – commanding the front line system – and it was to co-operate with some patrols of the Royal Irish Fusilier and Royal Warwickshire Regiment working up towards the Chateau. The bombing party worked forward along Corona trench until the trench came to a dead end which was much blown in, and here it established itself. The patrols that were working on its flanks having met with a good deal of opposition were unable to establish themselves to advance far.

Several small parties of the enemy were seen on the East side of the Roeux – Gavrelle Road by my bombing parties and a machine gun was located and reported.

In the meantime the enemy counter-attacked near the Chemical Works but our artillery dispersed them, though they were reported to have captured some of our advanced posts.

Enemy artillery had been fairly quiet after the counter-barrage had ceased, and for the remainder of the day the line remained inactive.

After dusk several small parties and individuals who had been lying in no-mans-land returned to the line, and it was ascertained that no one remained holding out in the neighbourhood of the Cemetery.

At 10 p.m. I received orders from Lt. Col Forster to establish a line of posts from I.19.c.6.6 to West edge of Cemetery. Work was to have commenced at 11 p.m. – but owing to the difficulty of getting my working parties organized, and as my orders did not reach the front line until 10.30-11 pm, work was not commenced until after 12 midnight. My orders were to dig a line of 9 posts at about 50 yards interval and to man them when they were complete. Owing to the fact, however, that the ground had not been previously reconnoitred by daylight with a view to digging the posts and that they were started somewhat hurriedly, the officer in charge took a wrong direction, and the posts were established in a more easterly direction than they should have been. On the following night, however, I had this rectified and the line as laid down was established and held.

The above completed the operation from Zero hour May 3rd until dawn on May 4th. During this time we suffered the following casualties:-

Officers |

Other ranks |

||

| Killed | 4 | Killed | 16 |

| Missing | 3 | Wounded | 91 |

| Wounded | 3 | Missing | 114 |

Total |

10 | 221 | |

Practically all of which were caused by machine gun fire.

For the bravery shown throughout the battle to take Roeux, the Household Battalion won a Military Cross and nine Military Medals. The capture of the tiny villages of both Roeux and Fampoux cost the Household Battalion more than half the original strength of the Battalion.

For the bravery shown throughout the battle to take Roeux, the Household Battalion won a Military Cross and nine Military Medals. The capture of the tiny villages of both Roeux and Fampoux cost the Household Battalion more than half the original strength of the Battalion.

On 30 May 1917, William was officially reported as "missing" on 3 May 1917. His wife was informed of this on 26 June. On the 21 July it was confirmed he had been "killed in action" on 3 May. This would have been as a result of his body being found and identified.

William is buried in the Roeux British Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France, Grave Ref: A 41.

The cemetery was made by fighting units between April and November 1917 and in it they laid to rest 350 of their comrades.

William's death was announced locally:

| Faversham and North East Kent News of 11th August 1917 |

DEATH OF A LYNSTED MAN Official news has been received of the death in France of Private William Gambrill, of the Household Battalion. Private Gambrill, who was 28 years of age, was the youngest son of Mr and Mrs Gambrill, of Lynsted Court. He formerly worked in the Sittingbourne Paper Mills. He joined the Buffs on June 8th 1916, and went to France on November 8th, afterwards being transferred to the Household Battalion. He leaves a widow and three children, who live in Greenstreet, for whom, as well as for the parents, much sympathy is felt. |

William's platoon leader, who wrote the kind words to his widow, Sec Lieutenant Oliver Wakefield, was himself killed in action on 12 Oct 1917.

William was posthumously awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medals. [See Appendix 1]

In September 1917, William's widow and children received his owed pay of £8 18s 3d (£8.91p). In January 1918, his widow, who was now living in Jeffries Cottage, Mill Lane, Lynsted, received the news that she had been awarded a pension, back-dated to 31 December 1917, of £1 6s 3d. In October 1919 she also received his War Gratuity of £3. [See Appendix 2] Taken together these amount to roughly £950 in today's money.

Lilian remarried in 1919 to Charles William Probert of Deerton Street and had another daughter, Marjorie, in 1923. Lilian died in 1947 aged 58.

William's brother George served in The Buffs and the Durham Light Infantry. He served in France but was discharged from the army after contracting malaria in Salonika. Both of William's parents are buried in Lynsted Churchyard extension.

William and another Lynsted casualty, Henry Carrier, whose biography appears next, have consecutive service numbers in the REKMR and only a few digits apart in the Household Battalion. They were possibly friends who had enlisted in the Royal East Kent Yeomanry together, or simply just next in line in the queue.

William is also commemorated in the regimental chapel of the Household Battalion in Holy Trinity Parish and Garrison Church, Trinity Place, Windsor.

Creekside Cluster Losses on 3rd May 1917

Thursday 3 May 1917 saw the heaviest casualties for Lynsted when 5 men were lost at the Third Battle of the Scarpe.

The stories of these 5 men follow similar paths. Amos Brown and Reginald Weaver both served in 6th (Service) Battalion, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment). Stanley Cleaver and MacDonald Dixon served in both the Royal East Kent Yeomanry (The Duke of Connaught's Own) (Mounted Rifles) and 7th (Service) Battalion, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment). William Gambrill served in both Royal East Kent Yeomanry (The Duke of Connaught's Own) (Mounted Rifles) and the Household Battalion, Household Cavalry and Cavalry of the Line, alongside Henry Carrier who was lost 8 days later on on 11 May 1917.

Three more men were lost that day from the Creekside Cluster. Harry Filmer, lost from Newnham, served in the 1st (Service) Battalion, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment). William Henry Laker, lost from Teynham, served alongside Stanley Cleaver and MacDonald Dixon serving in 7th (Service) Battalion, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment). George Potts, also lost from Teynham, served alongside Amos Brown and Reginald Weaver, 6th (Service) Battalion, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment).

Six of these eight men fell without a known grave and are recorded in Bay 2 of the Arras Memorial alongside 242 other men from The Buffs who perished that day. They are Amos John Brown, Stanley Monkton Cleaver, MacDonald Dixon, William Henry Laker, George Potts and Reginald Douglas Weaver.

World War 1 Pages

World War 1 Pages