"A Most Exquisite Artist" - The Work of Epiphanius Evesham - By Edmund Esdaile

[Shared with us by Dr Robert Baxter from an issue of Country Life, 11th June 1981 - adding a letter from Lynsted Historian A.J.W. Vaughan]

UNTIL half a century ago Epiphanius Evesham was but a name, unforgettable and tantalising, for in a single contemporary allusion he is called "the most exquisite artist" who had made a small, otherwise unrecorded memorial, a brass, in Old St Paul's. That was all, except a statement of 1818 that he had been a pupil in London of an Anglo-Dutchman, Richard Stephens. Then, suddenly, he was revealed as having indeed been a most exquisite artist, and within two or three years a number of major monuments, and minor works, signed and attributable, became known. It is with two major monuments both in Kent, that we are concerned here.

UNTIL half a century ago Epiphanius Evesham was but a name, unforgettable and tantalising, for in a single contemporary allusion he is called "the most exquisite artist" who had made a small, otherwise unrecorded memorial, a brass, in Old St Paul's. That was all, except a statement of 1818 that he had been a pupil in London of an Anglo-Dutchman, Richard Stephens. Then, suddenly, he was revealed as having indeed been a most exquisite artist, and within two or three years a number of major monuments, and minor works, signed and attributable, became known. It is with two major monuments both in Kent, that we are concerned here.

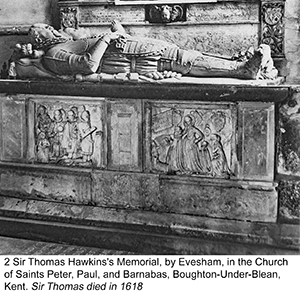

These adorn the churches at Lynsted and Boughton-under-Blean, west of Canterbury; the former commemorates Christopher Roper, 2nd Lord Teynham (d. 1622), and the latter Sir Thomas Hawkins (d. 1618). Lord Teynham's has been handsomely restored by Maurice Keevil, whose photographs I gratefully acknowledge. Both monuments, since they were rediscovered, have been more than once treated in print; but their historical value, although not overlooked, has taken second place to their artistic merit. Detailed study, however, shows them to be hardly less remarkable historically.

The earlier of the two is that at Boughton-under-Blean. The Hawkinses, like the Ropers, were staunchly recusant - hence, as will appear, a seemingly trivial carved detail. Beneath the recumbent effigies of Sir Thomas and his wife are groups in high relief of their sons and daughters. Aymer Vallance rightly noted a "gift of grouping, which exhibits astonishing imagination and resourcefulness' totally distinct from the usual formal array of kneeling children (see Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. XLIV, based on the late Mrs Esdaile's information; the information here given is new).

Three of the sons are treated in The Dictionary of National Biography - Sir Thomas junior, translator, poet and one of Edmund Bolton's 84 nominees for his projected academy; Henry, a Jesuit, who also translated Horace and various French works; and John, a doctor, who wrote about hypochondriac melancholy and translated from the Italian.

Sir Thomas junior, as befitted an eldest son, wears armour; John is an evidently more academic figure; of Father Henry only the head and one hand are visible. But that single hand is uniquely raised, palm outward (the apparently trivial detail earlier mentioned); and what can be seen of him, correctly placed though he is as second son, is in low relief, the high relief of the third son being superimposed. The only explanation of this discreet withdrawal is that he is imparting his priestly blessing on his family. I know of no other portrait (and all the sons, except perhaps the deceased child holding a skull, seem to be portraits) of a missionary priest pastorally employed in England at a time when his very presence here was illegal.

Sir Thomas junior, as befitted an eldest son, wears armour; John is an evidently more academic figure; of Father Henry only the head and one hand are visible. But that single hand is uniquely raised, palm outward (the apparently trivial detail earlier mentioned); and what can be seen of him, correctly placed though he is as second son, is in low relief, the high relief of the third son being superimposed. The only explanation of this discreet withdrawal is that he is imparting his priestly blessing on his family. I know of no other portrait (and all the sons, except perhaps the deceased child holding a skull, seem to be portraits) of a missionary priest pastorally employed in England at a time when his very presence here was illegal.

This group of six adult sons, devout and unselfconscious, conveys a moving impression of family solidarity. They kneel close together, their equal scale varied only by the small figure of the deceased child, and the composition justifies all Vallance's praise. Viewed as a whole or part by part, it is both varied and firm; rich raiment is contrasted with plain armour and plain cape, the heraldic cartouche is not too emphatic, the mottoed riband, Vive ut post vivas, frames all and harmony is established without fuss.

The freedom with which the group of daughters is treated differs entirely. The brothers incorporate the family's sense, their sisters its sensibility. Their scale and their mien varies according to their disparate ages, yet in the sculptor's vision their diversity is unified.

The older daughters, whose postures art not identical, are welded into one by the constantly repeated, downward-curving parallel folds of their long skirts; as they grieve, they seem to sway gently on an incoming tide of tears. Only the married ones wear hats; each is heraldically identified by a shield, impaled or not as the case may be; there is even a minute cartouche on the infant's cradle.

By implication, both reliefs are visualised indoors, the heraldic display doing duty for pictures. On the left this display is completed by a drape apparently in the process of being hung like a tapestry; it bears the motto Nox vitae lux animae, a quotation which I cannot place - St Teresa or St John of the Cross?

At Lynsted are the same qualities of vivid portraiture, spiritual insight, variety in composition and detail alike, and mastery of relief. But instead of six sons there are only two and instead of an indoor scene, plain air and ample space. Both sons kneel, the elder, as before, in armour in front of his younger brother, who has left his hawking in order to pray. His hawk on its perch and his dog are behind him.

Of all these four reliefs, that of the Roper daughters is perhaps the most remarkable, and it is here that we are reminded of Crashaw's verse. The five daughters are fashionably dressed; most are décolletées they wear necklaces; and to assuage their grief they retain their lapdogs. Or so it seems. But when we recall an earlier Roper, William, who married Thomas More's daughter, Margaret, it becomes suddenly plain that those are not necklaces and lapdogs but rosaries and lambs of sacrifice, and that the women thus equipped must be nuns. The only one lacking these accessories is married and, as at Boughton-under-Blean, she wears a hat.

She whose head is veiled was Abbess of the English nunnery at Ghent; of the remaining three, the one standing behind the Abbess and who is differently clad died as a novice. Plein air is again the setting, but now it is a vision of Heaven; the clouds are full of winging angel-heads and the ladies are rapt in contemplation. They form a second unique group, this time of women - Lynsted's counterpart to Father Henry Hawkins and his brothers.

Secular dress was in those days enjoined as a matter of security on missionary priests for daily wear; for Mass, of course, they vested, the vestments and other necessities being carefully hidden. This did not apply to nuns who, apart from their inability to exercise priestly functions, remained in their convents overseas. Nevertheless, to show them clad like Father Hawkins in secular dress suited Evesham's purpose. As we contemplate these two Kentish monuments, his artistry and insight and our own insight into their whole context, sacred and secular alike, becomes increasingly vivid and touching.

Evesham himself remains a mystery. He and his twin, born in 1570, were the youngest of the 14 children of a Herefordshire squire, all no doubt Anglicans. But fact remains that it was to him that, in the last years of James I, was entrusted the task of making these memorials. How, we may ask, did he achieve this perfect participation in the inmost sanctum of other peoples conscious being if he did not himself share it? And how did the Hawkinses and the Ropers know that he could be safely commissioned? On both counts history is silent. Perhaps (this is but a guess) he was a "church papist", outwardly Anglican but, for whatever reason, unable or unwilling to avow his true convictions, who here used sculpture to express his heart's desire and who WAS given these opportunities of doing by two discreet and sympathetic Kentish families. We may never know whether this guess is, or is not, correct. What we do know is that Epiphanius Evesham was a great Renaissance master of religious art, that here, in marble carved when Crashaw was yet a child, Evesham anticipates his verse and that, in the last analysis, this is enough.

The first that anyone knew of his work, as well I remember, came at breakfast over the eggs and bacon when my mother opened a letter from the late Ralph Griffin, FSA, and before our astonished eyes, photographs of the 2nd Lord Teynham's monument were revealed. It was an incredulous moment; like stout Cortes we gazed at each other with a wild surmise. New and unsuspected waters lay before us.

Illustrations: 1 Maurice E. Keevil; 2 National Monuments Record.

Letter in response to the Article by local historian - Tony Vaughan

"A MOST EXQUISITE ARTIST"

SIR - Edmund Esdaile's article on Epiphanius Evesham (June 11) rightly identifies him as a great Renaissance master of religious art. This is even more strikingly illustrated in the Roper Monument in Lynsted Church than Mr Esdaile may have realised, for when the panel (Fig 5) is closely studied in conjunction with the known facts about the five daughters of Lord Teynham, a spiritual dimension in the carving is distinctly apparent. The kneeling Abbess of Ghent, on the extreme right, wearing her rosary, appears to be praying with quiet composure, her eyes wide open, turned heavenward; on the extreme left, her novice sister, the only other figure wearing her rosary, gazes outwards with a smile of quiet confidence.

Both suggest the joy of Resurrection, while the three central sisters who married are reacting to grief in the exaggerated conventional forms of the period. Seen in this light, the skill of Evesham's grouping is even more moving; it emphasises all the more the spiritual detachment of the two religious figures.

It may interest your readers to know more about the lives of these sisters; of the three central sisters, Bridget married Sir Robert Harleston of Cambridge, Catherine Sir Robert Thorold of Lincoln, and Elizabeth married (in turn) two Irishmen, John Plunkett and Walter Bagnal (see Hasted's Kent).

Dame Mary Roper was received into the English Benedictine Monastery at Brussels in 1617, when she was only 18, and was one of the four nuns sent from there in 1624 to found the Benedictine Abbey of Ghent, of which she later became the third Abbess. She was distinguished by her modesty, devotion and charity. During her last illness, only a month before her death, she received the young King Charles II, still in his coat mourning his father", as he passed through Ghent on his way into exile, and had "a serious and private conference with his Majesty, she noting down what pass d between them; where she did not spare to speak plainly and most piously in order to his eternall and temporall Good". The Kind was so impressed by her sincerity and humility that he sent his own doctor from Holland to attend her when he heard she was in danger.

Her sister, Margaret, was professed in 1628, when she took the name Scholastica. Despite an illness which she endured with great patience for 12 years, she was said to have "ever a sweet and peaceable disposition".

Not shown in the monument is the daughter of William Roper, the younger son shown in Figure 6, who was Lord Teynham's granddaughter. Mistress Catherine Roper was sent to her aunts in the Convent at Ghent at the age of 12. After two years, she felt a vocation to be a Poor Clare, but she was of too "delicate and tender a disposition"; a "gentle fever" intervened, and she died. She "was buried in a fine white Linnen habit girt with a St Francis Cord" - looking "most delicate fair . . . like one in a sweet sleep". (Obituary Notices of Nuns of the Benedictine Abbey of Ghent, published by the Catholic Record Society.) - A. J. W. VAUGHAN, Bumpitt, Lynsted, near Sittingbourne, Kent.